Know your Wildfowl

A knowledge and understanding of wildfowl and their habits is an essential to wildfowling, and accurate bird identification is a core skill of the wildfowler. Accurate quarry recognition is essential, and it must be perfected not only in broad daylight, but in the half-light of dawn and dusk, which is when most wildfowling takes place. Experienced wildfowlers are able instantly to recognise their quarry from its silhouette, its call and even the sound of its wingbeats. To do this takes time, and there is no substitute for patient hours of watching ducks and geese in their natural habitat.

Ducks can be divided into two categories: the diving ducks and the surface feeding, or ‘dabbling’ ducks. Divers feed on invertebrate creatures which they find at the bottom of deep water, either big tidal estuaries, reservoirs or deep ponds. They are characterised by a slightly dumpy appearance, and their legs and paddles are set far back along their bodies to assist them when swimming under water. When in flight, the diving ducks have a distinctively rapid wingbeat. The diving ducks include Tufted duck, Pochard and Goldeneye. Dabbling ducks feed on or from the surface of the water, or graze upon vegetation close to the water’s edge. They have an elegant, streamlined outline, and are masters of the air. The dabbling ducks include Mallard, Wigeon, Pintail, Gadwall, Shoveler and Teal.

The quarry geese comprise the Pink-footed and White-fronted goose, both of which are migratory; the Canada goose, a feral species that has spread extensively from birds introduced to Britain in previous centuries and the Greylag goose, Britain’s only native breeding goose species. Canadas are easily distinguished by their great size, their long black necks and white cheek bars. The other species, or ‘grey geese’ are more easily distinguished in flight by their calls.

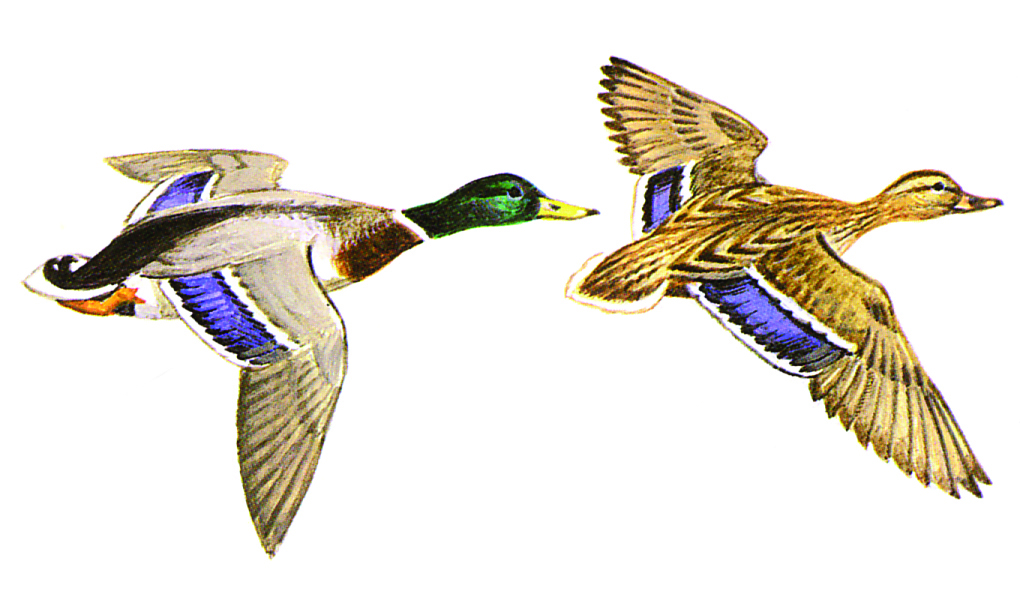

The ubiquitous mallard is found throughout the northern hemisphere, and is the ancestor of all our farmyard breeds. With its bottle green head, bright yellow bill, white neck band and blue-and-white speculum, the mallard drake is immediately familiar. He is accompanied by his more sober hued mate, whose plumage is brown, but who still carries the blue-and-white speculum on her wings.

Mallard are found wherever there is water, on rivers, lakes, marshes and estuaries. They breed throughout Britain, producing 10-12 eggs in a down-lined nest hidden close to the water’s edge at any time from midwinter onwards. In winter, the ‘home bred’ population is augmented by very large numbers of migratory mallard from Scandinavia, Iceland and the Baltic.

Preferring to feed in shallow water, mallard eat a wide variety of vegetable food, from grain to the exposed stems of water plants. They will quickly take advantage of frosted potatoes or spoiled grain left in the fields after harvest.

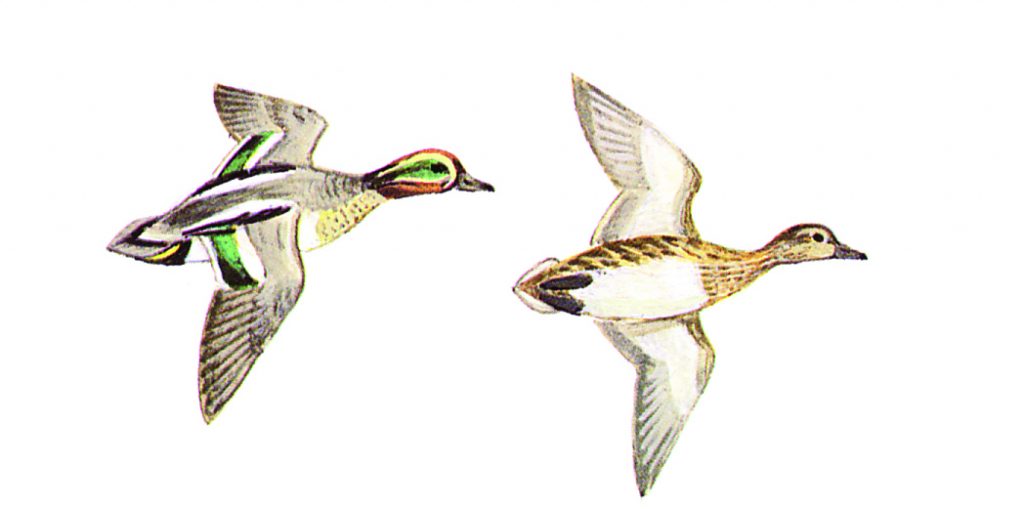

The teal is the smallest of the commonly encountered ducks and their diminutive size makes them instantly recognisable. The drake teal has a grey back, a speckled breast and a chestnut head with broad green eye stripe. His mate is brown, but shares his iridescent green speculum.

A few thousand pairs of teal breed in Britain, but the vast majority of birds which we see in winter are migrants, with many coming from Scandinavia, Russia and Iceland. They may be found together in large numbers, are very agile in flight, and when startled will rocket vertically into the air at great speed.

Teal are largely seed feeders and prefer to dabble for the seeds of marsh grasses and sedges, though they will also take invertebrates, especially in summer. Their note, which they make in flight, is a soft but distinctive ‘teep’.

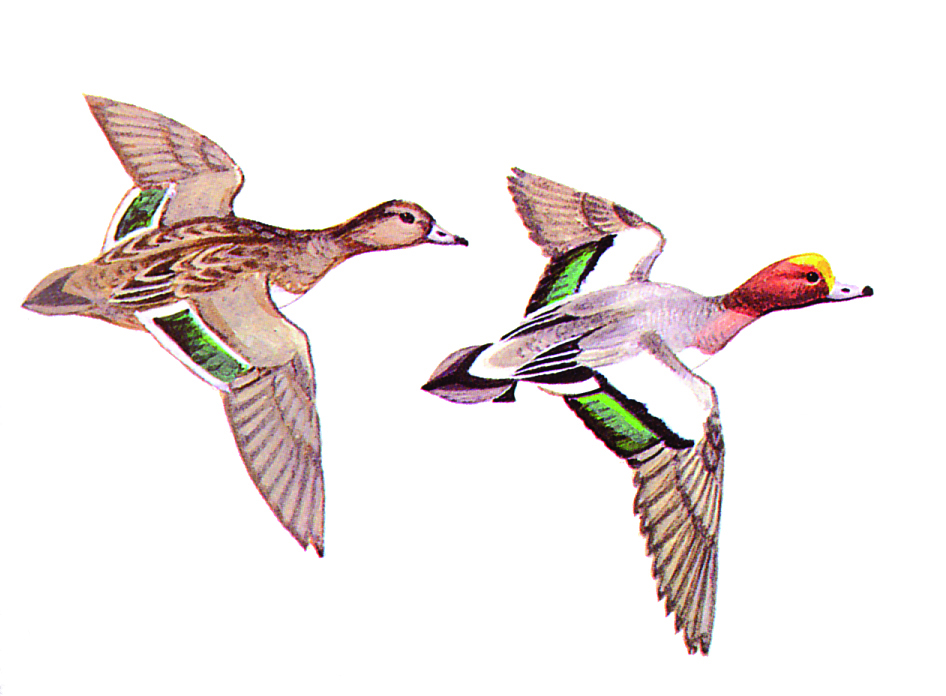

The wigeon is almost entirely a winter visitor to Britain, arriving from late August through to mid-November from its breeding grounds in Scandinavia, northern Russia and Iceland. The cock is particularly handsome in his grey plumage with white underparts, pink breast and chestnut head with brilliant sulphur-yellow forehead flash, while the hen shares her partner’s grey bill with black tip and metallic green and black speculum.

The wigeon is a grazing bird, which feeds on shallow flooded meadows and tidal flashes. It also occurs in large numbers where there is plenty of its favourite saltwater food, zostera or eelgrass. Wigeon are quick to exploit freshly flooded water meadows in late autumn and winter, and where the habitat is right, tens of thousands of birds can congregate on a single site.

The familiar whistling call ‘wheeoo’ is made by the cock birds both in flight and on the ground, while the hens contribute a low growling sound.

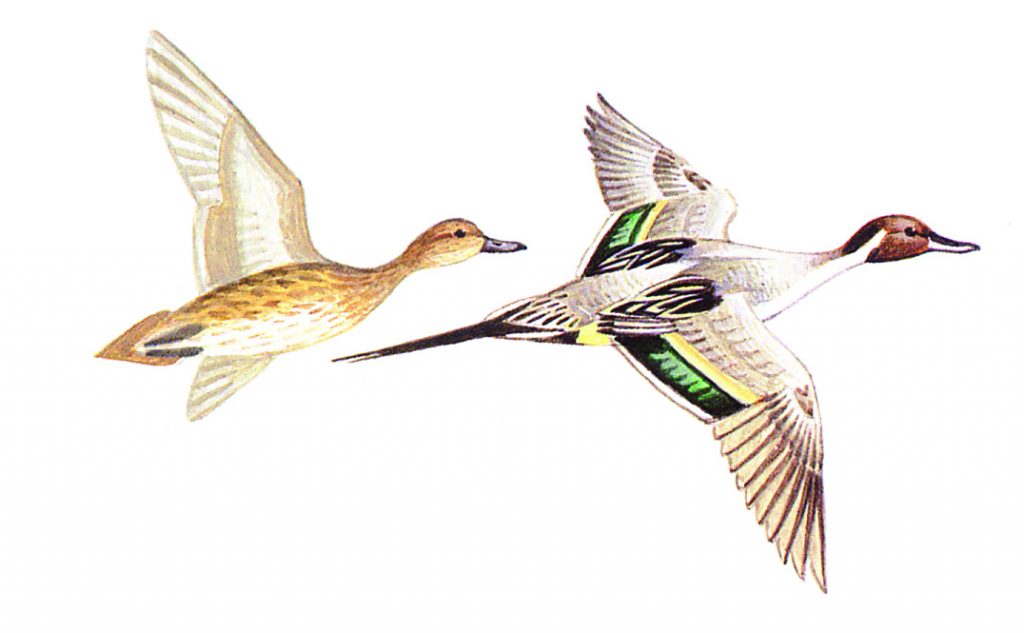

This elegant bird is one of the most abundant duck species worldwide. The female shares the graceful, elegant shape of the drake, but her grey-brown colouration cannot compare with his handsome chocolate brown head and white neck stripes. Nor does she have the highly distinctive long and pointed black tail feathers from which the species derives its name.

Pintail breed in a few isolated sites in Britain, but are mainly winter migrants, arriving in the autumn from western Scandinavia, northern Russia and Iceland, to overwinter mainly on coastal sites around the major estuary systems. The pintail feeds largely on aquatic plant material, but also takes invertebrates such as water insects, molluscs and worms.

The species can easily be recognised in flight by its long, outstretched neck and its long tail, coupled with its black and white colouration.

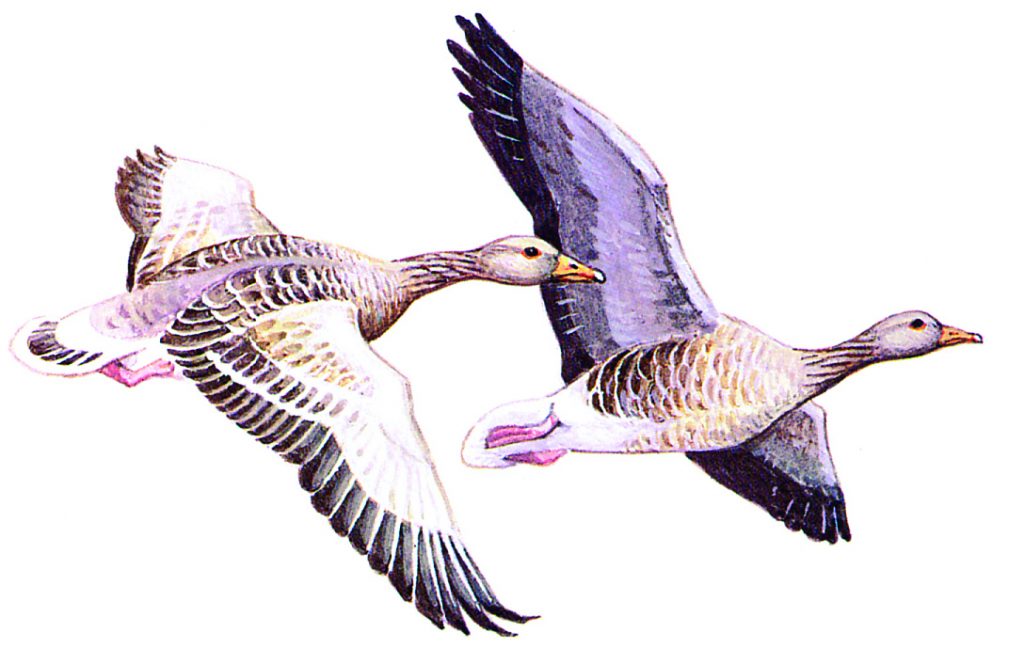

Britain’s only native breeding wild goose species, the greylag is the ancestor of most of our domestic geese. It occurs throughout the western palearctic zone, through central Siberia to Japan, although most of the migratory greylags arriving in this country in the autumn breed mainly in Iceland, with a few birds coming from western Scandinavia and the Baltic coast. Home bred greylags tend to remain fairly local in their habits, with significant concentrations of birds staying resident in the areas where they were raised.

It is not easy to visually distinguish the greylag from the other grey geese at a distance, although identification marks to watch for are the pale grey-brown plumage of the head and neck, which extends down over the breast, and the orange-pink bill. Its voice, however, is distinctive: a deep bell-like ‘aang ung-ung’, which it makes in flight.

Natural grazers and foragers, greylags are partial to a wide range of agricultural crops, from grass through root crops and potatoes to winter cereals.

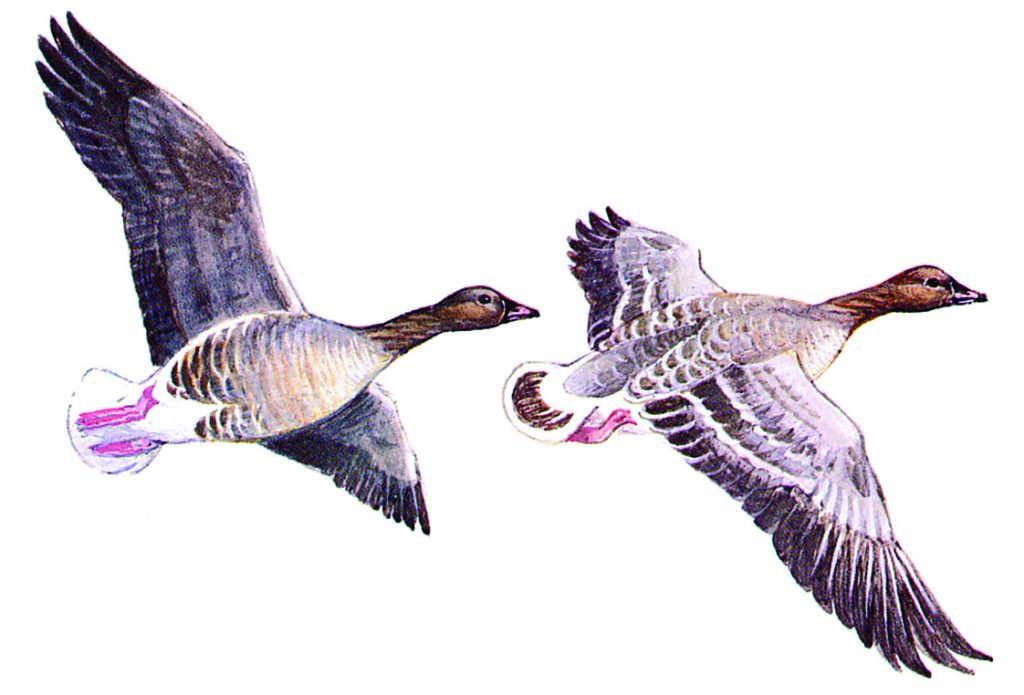

The pink-footed goose is the smallest of our grey geese and arrives in the autumn from its breeding grounds in Spitzbergen, Iceland and Greenland. It can be distinguished from the greylag by its size, by its browner head and neck and by its pink and brown bill. In flight, however, its characteristic call, a bright ‘ink-ink’, is a ready point of identification.

Like the greylag, it feeds largely on farmland, close to traditional coastal roosting sites such as the Scottish firths, the Lancashire coast, the Wash, and north and east Norfolk. It readily takes gleanings off the autumn stubbles before turning to grass, winter cereals, sugar beet tops and roots. Where vegetables are grown, pinkfeet also feed on carrots and a variety of brassica crops, often in very large flocks. As with the other grey geese, the pinkfoot is steadily increasing in numbers, and the population is currently buoyant.

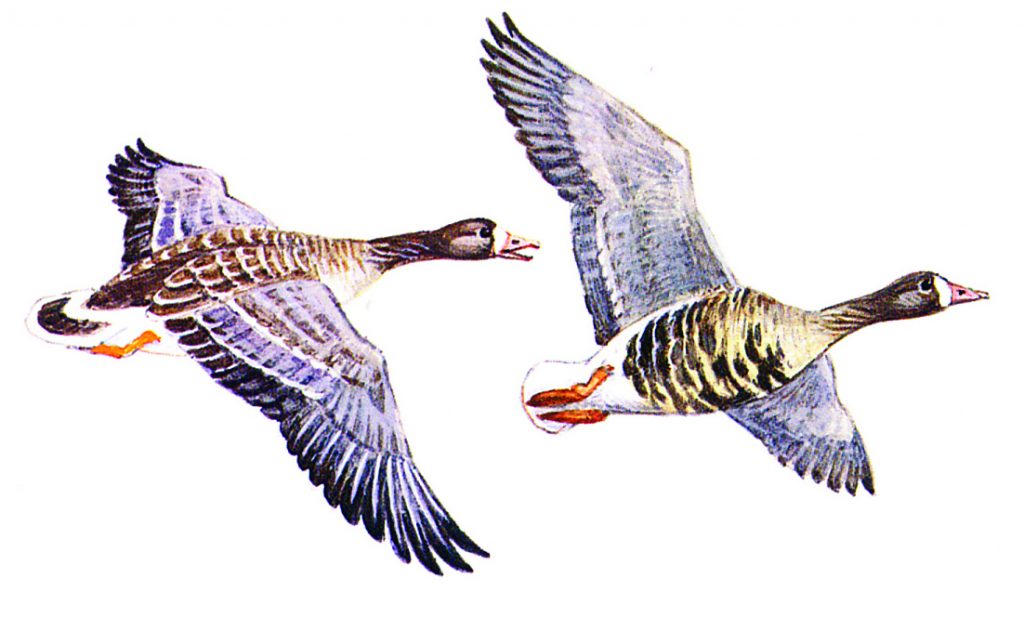

The white forehead and black-barred underside are the key distinguishing features of this medium sized grey goose. A regular visitor to the Suffolk coast, the European race of this species breeds in the Arctic regions of north west Russia, migrating quite late in the autumn via the Baltic coast to winter in north Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium and England. Numbers may not peak until February, when the birds are driven west by the colder weather.

The whitefront’s thrilling cry, which it makes in flight, is not unlike that of the pinkfoot but it is higher pitched and more of a gabbling staccato. The birds are almost exclusively vegetarian and feed on wet grass marshes and saltmarsh plants. Populations of the European white-fronted goose are buoyant, in contrast to those of the Greenland race, which breed in Greenland and winter in Ireland and Scotland, with a small wintering population in Wales.

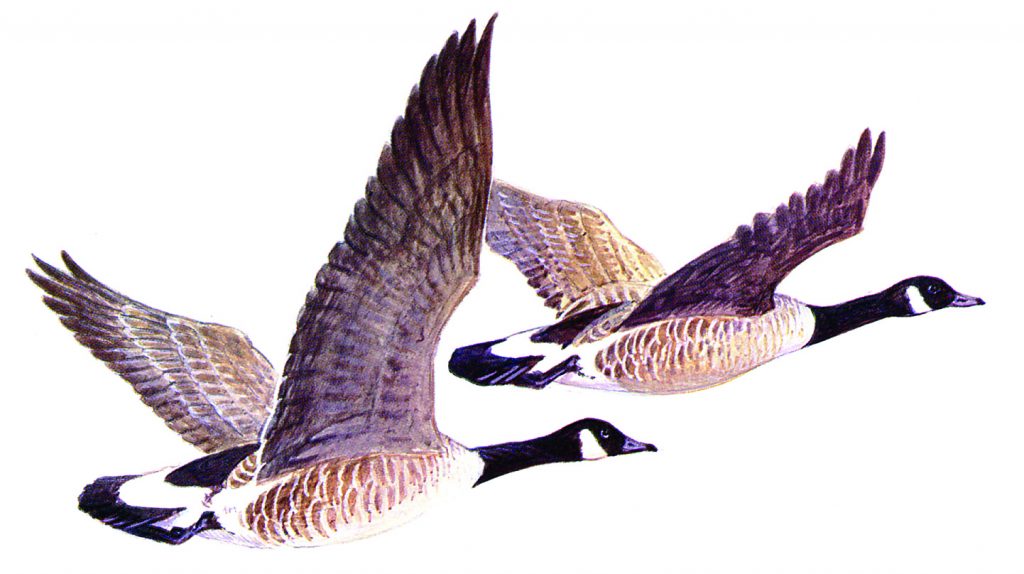

The Canada goose is our biggest quarry bird, and with its black neck, white cheek patches and grey-brown body plumage, it is immediately recognisable. In flight, Canadas make a distinctive ‘a-honk’ note, which carries over long distances.

This goose is not native to Britain but was introduced from America in the 1600s as an ornamental bird. It spread from the park lakes where it was first released and has now become well established throughout the country. Although Canadas in their native country are migratory, British populations tend to stay close to where they were raised. Canadas feed largely on grass and, like other geese, are on the increase.